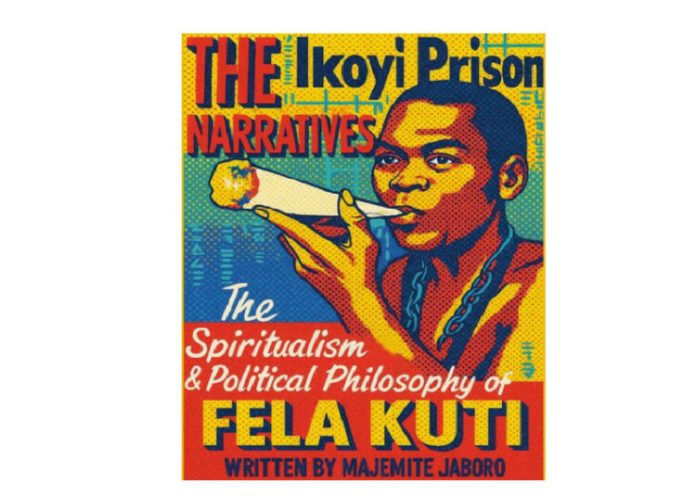

Book Review: Majemite Jaboro’s ‘The Ikoyi Prison Narratives’

The Ikoyi Prison Narratives Several publications have been written about Nigerian music icon, Afrobeat founder and activist Fela Anikulapo Kuti. However, none of those have arguably achieved what Majemite Jaboro’s ‘The Ikoyi Prison Narratives’ did, which is to intersect the man, his music, politics, and identity, situating them in Nigeria’s political history in a manner that illuminates the nation’s ongoing struggles with justice, freedom, and self-identity.

As an oral testament, ‘The Ikoyi Prison Narratives,’ written by Fela’s one-time disciple and Personal Assistant, Majemite Jaboro, documents his conversations with the revered musician during their confinement as roommates awaiting trial for a murder case in Ikoyi Prison, Lagos, between January and April 1993.

In weaving a compelling narrative, Jaboro introduces the reader to Yoruba history and spirituality, navigating the sacred landscapes of Oduduwa, Obatala, Sango, and Ifa divination. This is not mere academic instruction but a deliberate attempt at showing the reader Fela’s ancestral background, one of the many paths that informed his revolutionary ideologies, after he cast off Christianity, Marxism, and Western political concepts he grew up with.

Similarly, his visit to the United States in 1969, his immersion in the Black Power movement of African Americans, and his contact with the autobiography of American Civil Rights Activist, Malcolm X, shattered all forms of intellectual and emotional foundation he held at the time.

Brutally honest about Fela’s ignorance of African history before then, the author laid bare the painful conversations that sparked his (Fela’s) radical awakening. From that experience, Afrobeat was forged – as a conscious weapon; a music wielded not just to entertain but to educate, mobilize, and liberate. Afrobeat expresses the music icon’s ‘Blackism’ slogan. ‘Blackism’ is founded on the conviction that Africa’s path to freedom lay in the reclaiming of its own intellectual and cultural traditions, thereby unshackling itself from the chains of Western economic and political philosophies.

The reader understands the necessity of Fela’s ideology, as Jaboro digs into the brutal legacies of colonialism in Nigeria, the shattered dreams of her early independence, the catastrophic collapse of the First Republic, in addition to the bloody coups of 1966 and the resultant civil war. The reader also begins to perceive Fela’s rebellion not as mere romantic posturing but as a response to the concrete failures of governance, the corrupt elite, and the crushing brutality of military rule. By reopening Nigeria’s wounds, the author highlights Fela’s music as a defiant act of healing and a sonic resistance against oppression.

Nigerian Books Of Record Celebrates 5 Diaspora Legends With Hall Of Fame Entry

Certainly, such resistance is not without repercussions, as seen in the book’s account of the pillaging of Fela’s abode, Kalakuta Republic, by the military, among other losses. The man, however, counters by suing the government in court, and channeled his rage in the song ‘Sorrow, Tears and Blood’.

The author further recontextualizes Fela’s iconic songs, such as ‘Zombie’, ‘Alagbon Close’, and ‘Expensive Shit’ – beyond the intangible cultural heritage to raw, unflinching political records, sonic snapshots capturing the brutal truths the government sought to erase.

First published in 2011 and revised in September 2025, this revision can be deduced as the author’s dedication to objectivity and honesty, especially his unwillingness to make a saint out of the African music icon. This he does by revealing Fela’s darker impulses. From his sexual domination, drug-fueled excesses, to his authoritarian grip on Kalakuta, and his messianic self-image that bordered on hubris. Thus, creating a nuanced portrait that resonates with the messy human truth.

Conversely, just as the revised edition does not sufficiently address those darker impulses, it also edited out a controversial aspect of the maiden edition, concerning the murder allegation. Perhaps the author believes that what was revealed is enough to invite the reader to grapple with the contradictions of the man and confront the flaws behind the myth, as all other humans have.

Although immersive, the author’s oral-history narrative style is simultaneously repetitive. It digresses at times to the point of disorienting readers for a bit. Scholars may bristle at the loose-handling of sources, and editors would have wielded a firmer hand. Contrarily, these imperfections separate this raw, counter-archive publication, which privileges the messy, subjective truth of lived experience, over the sterile certainties of official records.

‘The Ikoyi Prison Narratives’ is not just a book about music, or a nostalgic homage. It is a vital unsettling intervention in Nigeria’s ongoing conversation with itself. It is a clarion call to confront the truth that lingers, unaddressed, in the shadows of power; a reference source to understanding the complexities of a nation wrestling with its destiny.